by Sachin Makani, EVP of Scientific Strategy and Communication

“Behavior is the end result of a prevailing story in one’s mind: change the story and the behavior will follow.”

― Dr. Jacinta Mpalyenkana

In the world of medical communication, we are regularly tasked with changing the behavior of a group of people, usually health care prescribers in a certain disease area. What is the most effective way to achieve the desired behavior change? We know that television commercials directed at the layperson will not move the needle for a physician audience that wants detailed, evidence-based information on efficacy, safety, and dosing.

Enter peer-to-peer programming, in which highly-regarded specialists and thought leaders in that field deliver the message, sometimes to a live audience, other times in a virtual broadcast or video. What should the message actually be? Such presentations are often stuffed with large blocks of text and graphs shoved against each other, without much thought going into what the audience will experience.

Anyone who’s lived around other humans knows that old habits die hard, and trying to change someone’s behavior with the presentation of data alone doesn’t do the trick very well.

As a case study for how to do it better, we turn the clock back to WW2, where a scientific story, properly told, changed the course of history.

Some context: it’s the late 1930s; Germany has just invaded Poland and is on track for more. Simultaneously, the field of nuclear physics is undergoing a revolution, with scientists in Europe and the US having discovered it’s possible to split the atom (ie, fission). Some predicted that, under the right conditions, it may be possible for fission of one atom to cause fission in two others, leading to a chain reaction that unfolds in fractions of a millisecond. This could lead to the development of weapons with unimaginable explosive yield – the question was, which country would realize this potential and capitalize on it first?

With the “atomic chain reaction” still just an idea, academic scientists needed to get the attention of the US government, and fast, before Germany developed their own bomb. Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein each drafted letters addressed to President Roosevelt himself, to be hand-delivered by Alexander Sachs, economist and the president’s trusted adviser.

“’Alex,’ Roosevelt hailed across the Oval Office, ‘what are you up to?’

Sachs liked to warm up the president with jokes… now he told Roosevelt the story of the young American inventor who wrote a letter to Napoleon, proposing to build him a fleet of ships that carried no sail but could attack England in any weather, without fear of wind or storm. Napolean scoffed: ships without sails? ‘Bah! Away with your visionists!’

The young inventor, Sachs concluded, was Robert Fulton. Roosevelt laughed easily. Sachs cautioned Roosevelt to listen carefully: what he had now to impart was at least the equivalent of the steam boat inventor’s proposal to Napoleon.”

Szilard and Einstein’s prepared files, however, “[did not suit Sachs’ sense] of how to present the information to a busy President. ‘I am an economist, not a scientist, but I had a prior relationship with the President, and Szilard and Einstein agreed I was the right person to make the relevant scientific material intelligible to Mr. Roosevelt. No scientist could sell it to him.’”

Instead, Sachs read his own 800-word summation, “the first authoritative report to a head of state on the potential of using nuclear energy to make a weapon of war. It emphasized power production first, radioactive material for medical use second, and ‘bombs of hitherto unenvisaged potency and scope third.’” And it recommended specific next steps: (1) making arrangements with Belgium to secure uranium supplies, (2) expanding experiments to make fission possible, suggesting that American industry and private foundations would foot the bill (it was the US government that ultimately did so, a bill that spiraled into today’s equivalent of $23 billion). (3) he proposed that Roosevelt appoint an individual and a committee to act as liaison between the administration and scientific community.

Finally, Sachs closed out by reading a segment from Francis Aston’s “Forty Years of Atomic Theory”, putting special emphasis on the last paragraph:

Personally, I think there is no doubt that sub-atomic energy is available all around us, and that one day man will release and control its almost infinite power. We cannot prevent him from doing so and can only hope he will not use it exclusively in blowing up his next-door neighbor.

“’Alex,’ said Roosevelt, quickly understanding, “what you are after is to see that the Nazis don’t blow us up.’

‘Precisely,’ Sachs said.

Roosevelt called in Watson. ‘This requires action’, he told his aide.”

And the rest is history.

Of note, this is not a commentary on whether developing the atomic bomb was right or wrong, but rather a how-to guide on how to move another human into real behavior change.

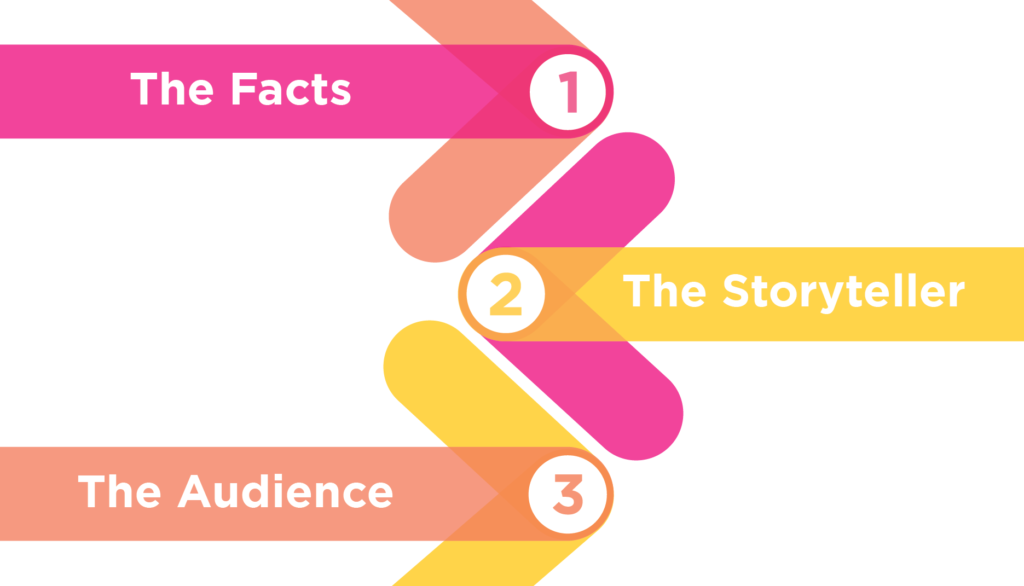

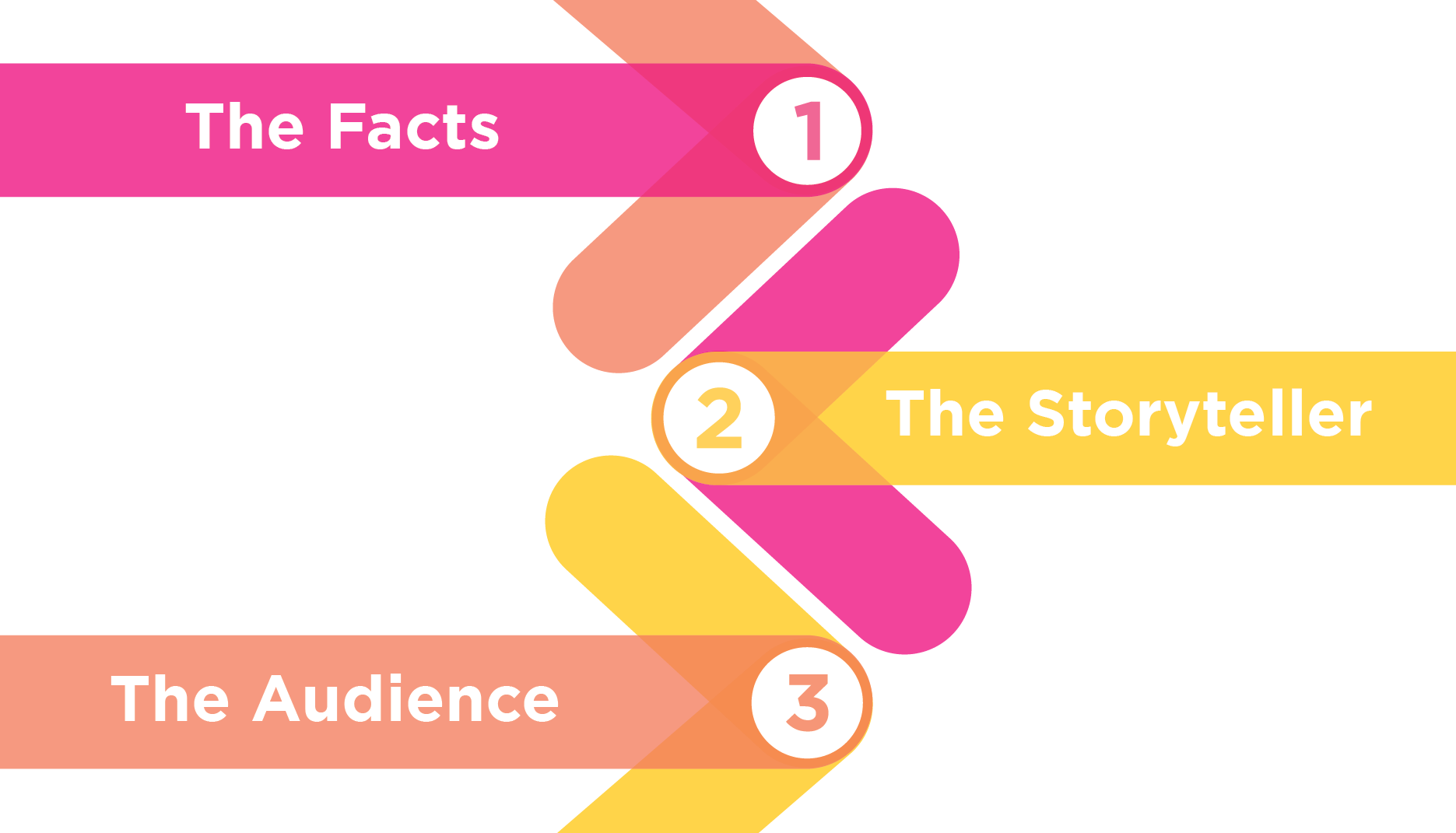

What can we learn from Sachs’ approach to storytelling?

- First, humans are hardwired to receive stories, not a linear presentation of facts – but it needs to be done well. When asked to simply throw a deck together, it’s worth considering a “pause” to align on the right This could mean as little as an extra 60 min call with your client, or perhaps it warrants a cross-collaborative, full-day workshop.

- Pay attention to your audience. What do we know about them? What do they believe/feel now, vs. what we want them to believe/feel? How can we leverage that information into our “storycraft”?

- In what medium will the story be delivered? Live or virtual? Is there an opportunity to pull the audience into the experience?

- Who is delivering your message? How will s/he be perceived by the audience?

- How is your story organized? In what order should the components be presented? How much time do you have to present it?

- What is the call to action? How do we draw bright lines connecting the story and those specific actions, and make it easy for your target audience to say “yes”?

Happy storytelling ?

PS. For a more detailed account of these events, I cannot recommend Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1995) highly enough. Though scientific history, you’ll inhale it, as you do the best of stories.